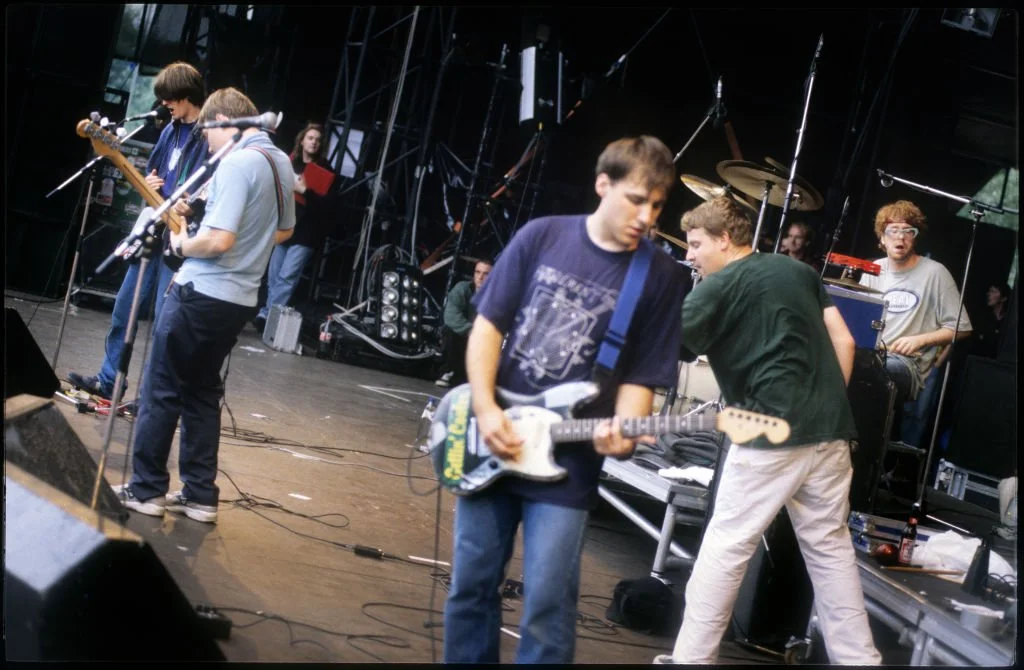

Pavement’s “classic” early lineup: Bob, Gary, Malkmus, Mark, Spiral

Author’s note (post updated 9.18.25):

Some factual corrections in this piece were kindly provided by Pavement’s Scott Kannberg after publication. Specific updates include clarifications on the band’s early history (Bag O Bones, Crisis Alert, Straw Dogs, Lake Speed, and Ectoslavia), the Nigel Godrich anecdote, and how Scott learned of the breakup. I’m grateful to Scott for taking the time to set the record straight.

I’m also excited to now offer my cover of Pavement’s “Date with IKEA,” one of my favorite songs by the band and written/sung by Sprial. Listen and download for free on my Bandcamp page or right here.

MUSIC VIDEO ADDED 10.23.25 - And don’t forget to check out my new music video for my cover, too. While you’re there, subscribe to my YouTube channel.

"This is what it's like to be in a band all these years"

On November 20, 1999, at London's Brixton Academy, Pavement played what turned out to be their final show for many years. It didn't end with a triumphant encore or a heartfelt goodbye, but with Stephen Malkmus shackling himself to the microphone with a pair of fuzzy handcuffs. He looked at the crowd and announced, "These symbolize what it's like being in a band all these years." It was funny, sad, awkward, and absurd—exactly the kind of exit you might expect from a group that had spent a decade thriving on irony and tension.

The handcuff stunt didn't come out of nowhere.

By the late '90s, Pavement was unraveling. The recording of Terror Twilight with producer Nigel Godrich had put most of the focus on Malkmus, leaving the rest of the band feeling sidelined.

"Nigel wasn't interested in anything else," Bob Nastanovich later said. "He didn't know any of our names. He just wanted to work with Stephen." Kannberg, whose songs once balanced Malkmus's, found his contributions pushed aside. Mark Ibold described the atmosphere as "weird and uncomfortable," while Bob Nastanovich admitted, "It was obvious Stephen didn't want to do it anymore." Steve West remembered Malkmus sitting on the tour bus with a coat over his head, calling himself "the little bitch." Years of touring had worn them down, and the simmering resentments—about who controlled the songs, who got credit, and who was just along for the ride—were finally boiling over.

By the time they walked onstage in Brixton, everyone knew it was close to the end. Malkmus had already told friends after Coachella earlier that year that he was finished. The handcuffs were less a gag than a signal: he felt trapped by Pavement, and he wanted out. Scott has said Stephen eventually called him to break the news he was done, though the whole thing still felt abrupt and cryptic.

Nastanovich was more philosophical, saying there wasn't much emotion left, just exhaustion, and that Malkmus's checked-out presence spoke louder than any conversation could. Malkmus himself offered little explanation, slipping quietly into the Jicks soon after and distancing himself from Pavement's mythology.

So the band that defined '90s indie rock went out with a half-joke and a cryptic performance-art gesture. Not a blaze of glory, but a strange, anticlimactic fade-out that still nags at fans two decades later.

One has to wonder if there was some specific incident that made Malkmus (SM) pack those handcuffs that day. It was premeditated performance art/band murder.

Why did their legacy implode this way? That's the question we're going to explore.

“Their breakup was so weird. I think for like 5 months after the handcuff incident it was hard to figure out what was going on. Their website had a bizarre string of updates about an upcoming live album that eventually was canceled because of a car accident? (There was also hope when they had two songs on the Grand Royal Groovebox comp but I think it turned out that was just Malkmus solo). Then suddenly it was just a blank page with a small message that said they weren’t a band anymore.”

How it starts: "We should do a Pavement cover"

I've always liked Pavement. But lately I've become obsessed.

I do this… I pull up some band everyone already knows and binge-listen and deep dive research for months on end. It's the OCD musician and fan in me.

I don't remember what got them back on my radar, as opposed to on the back of my mind. I think it's because I've been in a '90s cover band these last several months, and we're always coming up with covers we want to do.

Eventually, I thought of Pavement, and realized that, given the time, I'd love to cover a number of their songs. There was some resistance at first, since we're usually leaning toward more recognizable stadium banger type of stuff… Nirvana, Hole, Silverchair, Foo Fighters, Green Day, Weezer, Pearl Jam, etc.

I wasn't surprised to learn that like most people who lived through that era, the guys thought of Pavement as a '90s afterthought or B-side of sorts. Whereas in my mind, they were the best the '90s had to offer (along with Nirvana, of course). This was actually only much more solidified for me more recently, which is what compelled me to write this post.

I restarted my Pavement journey with the excellent Apple Essentials playlist to try to select a suitable cover, and it just opened up that whole OCD thing of bands I get obsessed with. I've been listening to Pavement only for the last few months since then. Like... everything they've recorded. It only deepened my appreciation for their catalog and what they accomplished.

More surprisingly, several of their songs started to make me feel something pretty rare, like wanting to cry and deep, profound joy at the same time. Tracks like "Gold Soundz," "Date with Ikea," and "Spit on a Stranger" to name a few. They're not sentimental, mass-appeal emo-pop dreck like the kind that acts like Adele, U2 and Coldplay seem to specialize in; there's something much deeper at play, at least for me.

I get the same feeling when listening to tracks like "So Lonely" by the Police, or "My Sister" by Juliana Hatfield. There's a certain combination of joy, craft, raw authenticity and intelligence at play underneath the lyrical and musical pathos. Some of these moments with Pavement just hit me like a bolt out of the blue—like listening to "Date with Ikea" for what might have been the first time, and I had to pull over my car (I emailed Spiral Stairs about this and he was kind enough to reply "It should've been a hit!" I agree, Spiral).

I originally wanted to cover "Cut Your Hair" since it worked for my voice, but our guitarist objected to the strange tuning of the second guitar. So I ended up choosing "Harness Your Hopes," a gem that was originally a B-side from their second album Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain that went viral not once but twice in the 2000s, revitalizing interest in the band with a whole new generation (more on this ahead).

Meanwhile, I was working on this post and watching their live and music videos, reading articles, listening, watching documentaries while trying to process it all without ruining that feeling, without overanalyzing what the band and the music means to me now.

It was a slow burn sort of realization… Shit, is Pavement my favorite band ever? Not just from the '90s, but from the whole batch of bands I grew up listening to and since then? Obviously this has so much to do with when you get interested in a band, along with social context. But for me, no other band left a musical legacy that's so deep and wide, and so utterly listenable on repeat.

So many songs, so many great ones. And so many that make me feel something I can't explain, to the point where I had to do some research. The feeling is called frisson.

I still don't want to ruin it, but I needed to figure it out the best I can. Hence this long-ass post, and me arriving at this theme of who are these guys? What happened? Why did it have to end?

There are so many "Pavement is the greatest indie (or '90s) band ever" pieces that to try to hammer that home much further wouldn't make much sense, so I wanted to explore how a band so good falls apart. It seems like they could've made records forever without repeating themselves.

Sure, it's guitar-driven rock (this is an oversimplification), there's a notable absence of harmonies, most songs end in three minutes or less, they add a lot of weird noise… but otherwise, there doesn't seem to be a set formula, which is part of their magic.

A band rooted in mystery

Some of the mystique surrounding the band was by design. Moves like crediting records to "SM" (Singer/songwriter/guitarist Stephen Malkmus) and "Spiral Staircase" (Scott Kannberg, co-founder and guitarist) might have been to protect themselves in case it failed. There was always the abstract and often beautiful cover art. Some of this was inspired by R.E.M.'s playbook, and I cover how to engineer this sort of anti-image in my book, Indie Rock 101.

But even bigger pieces of the band's mystery are rooted in their dynamic, their legacy, personalities and circumstance—and absolutely, most importantly their music. For me it's part of what fuels my continued fascination.

Aside from the personalities, one thing that struck me as I really went deep on the band was that they were not considered mainstream, even in their heyday. They're often described as having a "minor" hit on MTV with "Cut Your Hair" from their biggest-selling album, Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain (1994), which sold around 350,000 copies and featured their closest brush with mainstream success. While that record marked a shift toward a more accessible sound, it never propelled the band into true stardom. Despite critical acclaim and growing buzz, it fell short of the commercial breakthrough some expected, solidifying Pavement's role as cult heroes rather than chart-topping rock stars.

Was the fact that they never hit the mainstream tragic or the way it should be? What was with this old hippie Gary Young being part of the band? Why did Stephen eventually distance himself from the band near the end of their tenure? What issues were there for him, or between the group that made him do a silent breakup versus explaining what was up? What was Bob Nastanovich's role, exactly?

The more I learn, the more I understand that the answers to these questions might always be incomplete to an outsider, likely even to the band itself. And the "answers" always seem complicated, especially when you hear each member of the band interviewed separately.

A somewhat brief history

Skip ahead if you are a Pavementhead, you probably already know this stuff but it's important context for those who aren't familiar

“Pavement was originally a pathetic effort by us to something to escape the terminal boredom we were experiencing in Stockton.””

The whole thing started because two college kids in Stockton were bored. Stephen Malkmus and Scott Kannberg first connected in the mid-’80s, drawn together by their shared obsession with underground bands like Sonic Youth and the Minutemen. Stockton wasn’t exactly a hotbed of indie rock—it was more known for agriculture and suburban sprawl—but that isolation might have been exactly what they needed. No scene to impress, no expectations to meet. Just two friends with guitars and too much time on their hands.

Before Pavement officially took shape, Malkmus and Kannberg dabbled in side projects with friends. One of their running jokes was telling people they were in a fake band called Crisis Alert (a pretty great band name, even if it never existed). More concretely, they played together in Bag O Bones around 1985–86 while taking a break from college. When Kannberg spent a year at Arizona State, he began recording under the Pavement name (1986–87), sketching out the first ideas that would evolve into the band. Back in Stockton, they tapped into a small circle of local musicians—Malkmus had played in Straw Dogs during high school, while other friends cycled through groups like Lake Speed at UVA and the half-real/half-mythical Ectoslavia.

The real breakthrough came when they crossed paths with Gary Young, a guy in his forties who ran a home studio out of his garage and had that perfect combination of technical knowledge and complete lack of commercial instinct. Young wasn’t just some session drummer they hired—he was a true believer in whatever weird sonic experiments they wanted to try—and crucially, Scott was the one who made it all happen practically—borrowing money for studio time, designing covers, mailing packages to labels.

“I think, compared to a lot of other new bands, people can see that much of this is an accident. There’s no concept of being a big band... I didn’t put an ad in the paper, we just happened to go to a studio, when we made our first single and that was gonna be it.”

Those early recordings with Young capture something you can't fake: the sound of people who don't know they're making history. The drums sound like they're recorded through a tin can, Malkmus's vocals are buried in the mix, and half the guitar parts sound like happy accidents. But underneath all that lo-fi messiness was something genuinely new—songs that were simultaneously sloppy and sophisticated, drawing from punk's energy and art rock's experimentation without feeling beholden to recreate either.

The three EPs they made with Young—Slay Tracks (1933-1969), Demolition Plot J-7, and Perfect Sound Forever—started circulating through the tape-trading networks that kept underground music alive in those pre-internet days. Critics at Spin and other taste-making publications started taking notice. Gerard Cosloy at Matador Records heard something special and offered them a deal. Just like that, a bedroom project became a real band.

““This Malkmus idiot is a complete songwriting genius.””

Slanted and Enchanted (1992) was supposed to be those early tapes cleaned up for proper release. Instead, it sounded like the most beautifully damaged thing anyone had put out in years. The production was still primitive—Young insisted his drums sounded fine as they were—but Malkmus's songwriting had evolved. Tracks like "Summer Babe" and "Here" had actual melodies buried under all the noise, and his lyrics, while often cryptic, had a wit and intelligence that separated them from the grunge pack. The album didn't sell much at first, but the right people were listening.

Success meant change, whether they wanted it or not. The trio relocated to New York, where Malkmus took a security guard job at the Whitney Museum—not because it was romantic, but because it was one of the few gigs that would let him tour when needed. More importantly, they started thinking like an actual band.

Mark Ibold, who'd been playing bass in various NYC noise outfits, joined up and immediately made everything groove harder. Bob Nastanovich came onboard as a second percussionist, partly to help keep Gary Young's erratic timing in check, but mostly because he brought an anarchic energy that perfectly complemented their controlled chaos.

This five-piece lineup had chemistry you couldn't engineer. Malkmus and Kannberg's guitars worked like a conversation, trading off melodic lines and noise bursts. Ibold anchored everything with basslines that were simple but never simplistic. Nastanovich added texture and pure enthusiasm, shouting along to choruses and hitting whatever percussion was lying around. And Young behind the kit was like lightning in a bottle—completely unpredictable but somehow always exactly what the songs needed.

But even this magic couldn't solve the fundamental tension between Gary's expectations and everyone else's reality. As the band gained momentum, Young started pushing for bigger things—major label deals, mainstream success, the kind of money and fame that would justify all the touring and recording. The rest of the band just wanted to keep making good music without compromising what made them special in the first place.

The breaking point came after Slanted and Enchanted established them as indie rock's newest darlings. Young, encouraged by family members, started shopping around for that elusive million-dollar deal. He couldn't understand why they'd want to stay on Matador when major labels were calling. To him, it felt like his bandmates were holding back their own success. To them, it felt like Gary was missing the entire point of what they were trying to do.

His departure wasn't sudden—there were arguments, ultimatums and eventual acceptance that they wanted different things. Gary left, and with him went some of the beautiful unpredictability that had defined their early sound. But they also gained something: the ability to become the band they were meant to be without having to constantly manage someone else's chaos.

Steve West joins as drummer (top right) for the rest of the band’s career, career, career, career…

Steve West replaced Young behind the drums, bringing a steadiness that let the rest of the band explore more complex arrangements. West had met Malkmus while they were both working security at the Whitney—he had a practice space, Malkmus needed a drummer, and just like that, the classic Pavement lineup was complete. West's approach was looser than a typical rock drummer but more reliable than Young's explosive style. He gave them a foundation they could build on without losing the essential looseness that made them special.

Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain (1994) was their masterpiece, the album where everything clicked. They'd figured out how to be accessible without selling out, catchy without being obvious. "Cut Your Hair" was the closest thing to a hit they'd ever have, with its sardonic lyrics about the music industry wrapped in an undeniably great hook. "Gold Soundz" was three minutes of perfect indie rock, all jangling guitars and yearning vocals. "Range Life" was their gentlest song and also their most controversial, thanks to Malkmus's casual diss of the Smashing Pumpkins (Billy Corgan stayed mad about that for years).

The album proved that underground music could reach beyond its typical audience without losing its soul. But instead of building on that success, Pavement did what they always did: they zigged when everyone expected them to zag.

Wowee Zowee (1995) was their deliberate left turn, a sprawling, intentionally difficult album that confused fans expecting another Crooked Rain. It was experimental in the way that only a confident band could be—not showing off, but not caring whether anyone followed them into the weeds. Some of it worked brilliantly ("Rattled by the Rush," "Grounded"), some of it felt like inside jokes ("Serpentine Pad," "Motion Suggests"), but all of it felt necessary to them at the time. It was their most polarizing release, which was probably the point. “I was smoking a lot of grass,” SM deadpanned when musing over this record.

Brighten the Corners (1997) was the course correction, a return to the melodic focus that had made Crooked Rain so beloved. Songs like "Shady Lane" and "Stereo" reminded everyone why they'd fallen in love with the band in the first place, while tracks like "Embassy Row" showed they could still be confrontational when they wanted to be. It felt like Pavement had found their balance again—accessible but not pandering, experimental but not pretentious.

Their final album, Terror Twilight (1999), was different from everything that came before. Produced by Nigel Godrich, fresh off his work with Radiohead, it was their most polished and controlled record. The lo-fi aesthetic was gone, replaced by crisp production that highlighted every instrumental detail. But more significantly, it felt like Stephen Malkmus's solo album with backing from his bandmates rather than a true collaborative effort.

The recording process had been tense. Godrich was more interested in working with Malkmus than the rest of the band, and it showed in the final product. Kannberg's contributions were minimized, and the democratic spirit that had defined their earlier work was replaced by Malkmus's increasingly dominant vision. The result was still good—songs like "Spit on a Stranger" and "Major Leagues" were among their most beautiful—but it felt like the end of something.

And in many ways, it was. By the time Terror Twilight was released, the band was already fragmenting. The creative partnership between Malkmus and Kannberg that had started the whole thing was strained beyond repair. Touring felt like work rather than joy. The mystery and spontaneity that had made them special was being replaced by professionalism and expectations.

The end came not with drama but with exhaustion. After that final show in London, with Malkmus wearing handcuffs and making cryptic statements about the nature of being in a band, everyone just went home. No official announcement, no press conference, no explanation. Just silence where one of the best bands in the world used to be.

Looking back, their story feels both inevitable and tragic. Five albums in eight years, each one pushing in a different direction, each one proof that they were never going to be content doing the same thing twice. They created a template for indie rock that dozens of bands are still following, proved that you could be critically adored and commercially successful without compromising your vision, and then walked away before anyone could accuse them of repeating themselves.

For a band that started as a college-age experiment, that's not a bad legacy. But for those of us who lived through it, who watched them create something genuinely new and then deliberately destroy it, the questions remain: Why couldn't something so good last longer? And what might have been if they'd found a way to work through their differences instead of walking away?

Pavement's personalities (in order of entry)

4/21/94 on The Tonight Show with Leno. How can you not love a band that starts a song off this way? Although the band is tragicomic in some ways, they were just fucking crazy funny and weird in a way that seemed 100% authentic. I connected with Nirvana on this level, too. People forget how funny they could be in the sardonic lyrics and in many other respects before they became ROCK STARS.

I remember when I first started getting back into the band, I simply wanted to know more about their roles and personalities, let alone their dynamic. Again, if you are a Pavement head, you might not need this rundown, and you can skip ahead to more personal insights…

Stephen Malkmus — Vocals, guitar, primary songwriter

The reluctant frontman who never quite seemed comfortable with the role. Malkmus had the charisma and songwriting talent to be a proper rock star, but seemed actively allergic to the responsibility that came with it. His lyrics were cryptic but never pretentious, his guitar playing was sloppy but never careless. He had this way of sounding completely casual while pulling off incredibly sophisticated musical ideas—like he was letting you in on jokes you didn't even know were being told. The tension between his obvious talent and his resistance to using it conventionally was what made Pavement special and, eventually, what tore it apart.

Scott Kannberg (aka Spiral Stairs) — Co-founder, guitar

The unsung hero who deserves more credit than he gets. While Malkmus was the obvious creative force, Kannberg was the one who actually made things happen—the driver. He designed early cover art, handled correspondence with labels, managed logistics, and basically acted as the band's unofficial manager while also contributing songs and guitar parts that were essential to their sound.

“After recording was complete, Kannberg was tasked with releasing the music himself, as Malkmus had departed on a trip to parts of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Kannberg designed the cover of the EP and sent copies to various independent labels, distributors, and zines. He recalled, “I had no idea how to do it. I’d send off these little notes to my favorite labels like SST and Twin Tone and ask, ‘How do I do this?’””

Scott’s badass cover art for the Slay Tracks EP

His relationship with Malkmus was complicated—they'd grown up together in Stockton, where Scott was allegedly the “black sheep” who used to beat up the more sensitive Stephen. That dynamic seemed to carry over into the band, with Kannberg often feeling overshadowed despite being co-founder.

Gary Young — Drums

The wildcard who gave their early records their distinctive chaos. Young was older than the others, already in his forties when most of them were barely out of college, and he brought a perspective shaped by decades of recording in his home studio. His drumming was explosive and unpredictable—not technically perfect, but full of the kind of energy you can't teach.

Onstage, he was legendary for doing handstands, distributing vegetables and pennies to the audience, and generally stealing the show through pure weirdness. His departure after Watery, Domestic was Pavement's first real crisis, but he never seemed bitter about it. He kept making music and remained proud of his Pavement legacy until his death in 2023. He passed away in 2023 at age 70, and tributes from Malkmus, Kannberg, and others noted his eccentricity and foundational place in Pavement’s story—a legacy captured in the documentary Louder Than You Think.

“I’ve been doing this for years and no one paid a bit of attention. All of a sudden now I’m in this strange band. I don’t really understand the music, I’m curious about the lyrics, the songwriting part is beyond me. Whatever... I get drunk, I fall of the drum kit and drop my drumstick and they clap... I mean, what the fuck is going on? It doesn’t make much sense.””

Bob Nastanovich — Percussion, keys, yelling

The human exclamation point whose exact role in the band remains beautifully unclear. Officially, he played percussion and keyboards, but his real contribution was energy—shouting along to choruses, adding chaotic background vocals and generally making everything feel more alive.

Practically, he was their tour manager, van driver and morale officer. He kept the machinery of the band running while adding his own anarchic touch to the music. In interviews, he's the most philosophical about their breakup, understanding that all good things end and seeming genuinely grateful for the experience rather than bitter about how it concluded.

Mark Ibold — Bass

The stabilizing force who joined just as they were transitioning from interesting experiment to great band. His bass playing was never flashy, but it was exactly what their songs needed—melodic, steady, and locked in with whatever drummer they had at the time.

Before Pavement, he'd played in Dustdevils and other New York noise-rock bands, so he understood both the experimental side and the need for solid foundations. Personality-wise, he was the ultimate team player—easygoing enough to let others fight over creative control while he held down the low end and kept things moving forward.

Steve West — Drums

The professional who replaced Gary Young's beautiful chaos with reliable groove. West met Malkmus when they were both working security at the Whitney Museum—he had a practice space, Stephen needed a drummer, and the practical solution became the musical one.

His playing was looser than a typical rock drummer but more dependable than Young's explosive approach, giving the band room to explore more complex arrangements without losing their essential looseness. Unlike Gary, who seemed to struggle with the demands of being in an increasingly successful band, West adapted easily to whatever they needed from him.

Whenever a band member asks “What should we wear?” I say oh, jeans and a T-shirt is fine. The ‘90s ruled because it was no-bullshit with the good indie bands. No “stageclothes,” thanks. We had enough of that in the ‘80s.

My Top 10 songs: A Pavement primer

Before we go further, some more foundational info for the uninitiated—my Top 10 favorite Pavement songs, in loose but not rigid order.

This list is by no means complete (Here's my longer list on Apple Music I've been updating). I'll also qualify that while I love their earlier, "lo-fi" punk/noise/art rock kind of stuff, I'm more into their more melodic material, starting with their second LP, Crooked Rain.

"Stereo" (This might be my favorite song of all time if I had to pick one I have to listen to on repeat)

"Cut Your Hair"

"Gold Soundz" (This is often called "the best Pavement song," it is also a perfect song)

"Range Life" (a sonic diary entry of their time on the ill-fated Lollapalooza tour)

"Shady Lane/J Vs. S" (for me, this is one of several SM songs exploring themes of yearning and escape)

"Harness Your Hopes (B-side)"

"Date with Ikea" (sung and written by co-founder and second guitarist Scott Kannberg, an underrated gem; I'm working on a cover version)

"Embassy Row" (Just badass, one-of-a-kind and dangerous-sounding… a song that can't be copied)

"Unfair" (Similar edgy vibe, a sardonic love letter to our beloved home state of California)

"Spit on a Stranger" (Frisson every time. I don't know why but this song simply breaks my heart every time I hear it. It is a love letter, but never sentimental or cliche)

All of these songs are on the excellent Apple Music Pavement Essentials collection and a great place to start for some of their most iconic and enduring "hits."

They also have two compilations I'm aware of, Cautionary Tales: Jukebox Classiques and Quarantine the Past: The Best of Pavement. I actually prefer the latter as I feel it's extremely well curated, contains many rarities and presents the evolution of their sound in a thorough, if not chronological way. It's a great listen from front to back, but don't start there—the Apple Music Essentials collection is a better and more accessible place to start.

I understand that the band can be challenging for new listeners, especially their more raw, early material that draws inspiration from punk/dissonant/noise bands like Sonic Youth and Velvet Underground. This is where I find it helpful to keep going past Slanted and Enchanted and chronologically continue to tracks from Crooked Rain.

Comment on a Pavement video. 100% true.

Malkmus's lyrics have also been called cryptic and stream of consciousness, but they're impressionistic enough that for me and many others, they often express some feeling or idea in the best possible way. This is his gift as a lyricist and songwriter—words and music come together in a way that conjures an image or expresses a feeling in a way that only music can.

““Even though we don’t have classic, Bob Dylan lyrics, I think they have a tone that holds up better and is less cringeworthy than most other lyric writing. I don’t think any of my lyrics are literal. The way somebody’s voice sounds is much more important than how meaningful the words are.””

What surprised me throughout my deep dive into their canon is the creativity, variety, craft and sheer volume of SM's body of work while with Pavement. Not only was he incredibly prolific, but confoundingly consistent in the excellence of his craftsmanship. That's not to say that every Pavement song is a masterpiece, but Jesus, the guy wrote a shit-ton of great songs.

Most Pavement songs are deceptively simple but deeply layered in lyrical meaning, extra noise added to rough things up a bit (even in their more polished work), and the interplay between Stephen and Scott's guitars. It doesn't hurt that Steve West is an exceptionally versatile and solid drummer, along with bassist Mark Ibold, who are a huge part of Pavement's dynamic, especially in verses where they're holding things down.

I don’t recall the source exactly, but one listener theorized that Pavement was “creating love songs.”

I think that's too reductive a POV to apply to their entire canon, but for many of Pavement's songs where I feel that frisson I mentioned earlier, it's quite possibly true. It's one reason I think songs like "Here," "Gold Soundz" and "Spit on a Stranger" to name a few stand the test of time and make you feel something after repeated listens (Juliana Hatfield's "My Sister" will do this to me until the end of time because the lyrics hit me so hard, to cite one example). In these songs, SM or his narrator is singing to someone. There's a tenderness there laced with a bit of cruelty, and I suspect he can be this way in real life, the way the rest of us can in our best and worst moments.

The magic of great lyrics is that they're somewhat interactive. They're written by the artist, but the greats leave you some room to interpret and assign to your own life. The greats leave that mystery, that space. That's not nonsensical, it's by design. It's writing in code only the listener can crack in their own unique way.

I don't think the meaning of great songs are meant to be agreed on by everyone in terms of "what they mean." I know as a songwriter myself, I don't want you to know every detail about how the song came about. I wrote it for me, but I also wrote it for you.

The lyrics always mean something. If and when they don't, maybe they capture a fleeting feeling or a moment in time. For me, songs are time capsules. Love them or hate them, Pavement's songs are timeless.

While we're talking about loving or hating certain bands…

Why does Stephen Malkmus hate the Eagles?

In one interview floating around YouTube, Stephen Malkmus talks about the Eagles and similar bands with a mix of blunt disdain, comparing them to "a bunch of rich hippies chasing money" (he somehow manages to make even snark sound super-charming and funny). Hard to argue with that characterization, but at the same time, you can sense he begrudgingly respects their songwriting chops.

I don't want to put words in his mouth, but I've also heard him admit that songs like "Range Life"—and maybe even "Gold Soundz"—are, in a way, indie-rock versions of Eagles songs. If that sounds perverse, well... it probably is. He's said himself he wanted to sound more classic rock on Crooken Rain, "but good."

This falls under his quote about taking 80% inspiration from other artists, and adding 20% of your own, which honestly sounds very close to my own playbook as a songwriter. I can't speak for everyone else, but that's just the way it is. We love and draw inspiration from our heroes but we also want to make it our own.

What makes SM's comments about the Eagles even more relatable is that I went through my own phase with the Eagles. As a kid, I hated them. My father would blast them in the car and I thought it was just boring dad rock. But a few years ago, the OCD bug bit and I listened to them constantly, playing my own curated greatest hits over and over. I covered "Take It Easy" at the local open mic. Somewhere along the way, I realized those songs are insanely well crafted.

Maybe I just got old, too.

Pavement's first breakup was when Gary quit

Watching the Louder Than You Think documentary about Gary Young, I realized that his departure felt like Pavement's first breakup. It wasn't the end of the band, but it was the moment they hit a crossroads.

Stephen Malkmus has often cited Slanted and Enchanted as his favorite Pavement record. It has that raw, lo-fi purity—rough around the edges, dirty sounding, but full of charm. Gary might have bristled at people calling it lo-fi (since he recorded it), but that was part of its magic. By the time Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain rolled around, Stephen's songwriting had clearly evolved. By this point, they were semi-famous and had added two new members. The band was growing.

Young seemed to get them more than anyone at the outset. Even so, he was baffled by their success at the outset and seemingly throughout their career.

"When did you realize Pavement was a big deal?" his interviewer asks him on-camera in LTYT.

"After I left," he said, slumping down on his desk with a sad laugh.

““[Slanted and Enchanted]’s flaws are a big part of what makes it good. It’s not like some Radiohead record, where the whole thing is good. Our records aren’t good in that way. Our records are more attitude and style, sort of in a punk way. We’re good in the same way the Strokes are good. I think Slanted and Enchanted probably is the best record we made, only because it’s less self-conscious and has an unrepeatable energy about it.””

After Slanted and Enchanted bedazzled fans and critics alike, the band chose to stay with indie label Matador vs. pursuing a major label deal that could jeopardize their integrity and creative control. The more they kept the A&R people at bay, the more they wanted the band. It became clear the others were more about having fun and artistic credibility, but Gary had other priorities.

As the documentary shows, he shopped the band around for a million-dollar major label deal, encouraged by his father and brother, who told him not to "work for free." Meanwhile, the rest of Pavement wanted no part of it. They didn't want to chase Nirvana- or Weezer-style success. Malkmus himself admitted he could write hooks and choruses if he wanted, but the band's ethos was about the art, not chart success.

You can even see it later in an interview with Steve West and Mark Ibold. West openly acknowledges that more record sales would be nice, while Ibold's expression makes it clear that wasn't what Pavement was about. And in the Slow Century documentary, Bob Nastanovich flat-out says the band didn't think they could even deliver at that mainstream level. I disagree; Malkmus is clever and talented enough to have written big radio hits. But honestly, I'm glad he didn't.

Because of that choice, Pavement's legacy and artistic integrity remain intact. Sure, as a fan I would have loved five more albums, but what they left behind is a remarkably rich discography—far more prolific than Nirvana, even if Nirvana's handful of records are undeniably iconic.

So for me, Gary's exit feels like Pavement's "first breakup." After that, they shifted into the Steve West era, dabbled with more commercial sounds on Crooked Rain, pulled back with the art-rock of Wowee Zowee, and eventually arrived at Terror Twilight, which I think is underrated. To my ears, Terror Twilight foreshadows the Jicks—more controlled, more intelligent, less wild than Pavement's early years. Over time, I've grown to really appreciate it.

That first fracture, though, Gary leaving, set the tone. Pavement weren't going to sell out. They weren't chasing fame. They were in it for the music, and that's why their story, and their legacy, still resonates.

A few words about why Gary quit. We don't have to go too much into it since Louder than You Think covers it all so well.

I can see why he made his demands, even if they were unreasonable. The guy was in his 40s. His dad and brother were putting ideas in his head. He was tired from touring, maybe didn't see a present or future in all the hype and activity. He had the fame (at the time) but why weren't they rich yet?

Being a drummer is tough. It's part of the reason I knew in college I didn't want to be a supporting player. Not only was I a writer, but I knew that being the writer and singer afforded me the best chance of making a living with my music. Drummers are often taken for granted, they can get booted at any time (just look at the past few years—Jason Bonham, Zak Starkey and even top-tier pros like Josh Freese have all been cycled out of major gigs despite their pedigree). I think of Noel Gallagher ranting about how worthless drummers are in general in an Oasis documentary, which of course is offensive to me and unfair.

So yeah, as a drummer myself, if I were Gary, I probably would've felt the same way, especially in my 40s.

Let me be clear that I don't blame the band at all for the situation, I'm just saying I can understand what motivated Gary to want to pursue a deal and make crazy demands, even if he didn't go about it the right way and the demands themselves were beyond the band's ability to pay out.

Another sidebar here is that Steve West is a phenomenal drummer. He's solid and not flashy. Tight and loose at the same time. He does not overplay, he does not smash the drums. He keeps things interesting but most importantly he supports the song. His playing reflects my own approach. He's basically my dream drummer.

All of which makes the quiet breakup even more confounding. They all do what they do well, even if Bob's role is still a bit of a mystery to me, maybe even to Bob himself. Ibold's a solid bassist. Scott's a superb second guitarist (I love his advice to aspiring musicians in one of the documentaries "not to practice.") Stephen already had a great band to play his material.

So if you're SM, what were the issues?

Like...

Scott, you care too much?

Steve, you're simply too versatile and solid?

Mark, stop being such a good bassist?

Bob, don't blow all your money on horses and practice more? (These were apparently conditions SM set for Bob before embarking on their first reunion tour).

“They had always been a strange entity, less a band and more a collection of players orbiting around two songwriters, one a creative powerhouse who was at best ambivalent about the whole thing, and the other an enthusiastic driving force behind the group as a going concern.””

Obviously this commentary is tongue in cheek, and not really fair because there's always personalities, work styles, creative differences, money… any number of things can cause a band to implode.

“I was feeling the exhaustion of that... talking to that radio person in Portsmouth about this band Pavement that they never heard of because Domino [record label] wanted me to. And I was thinking am I going to have to do that again for the next album. We played bigger places than ever before on our last tour. There was something good about that, but also something unreal about it at that point. There were a myriad of reasons to quit, some of them aesthetic—it’s almost aesthetic to quit when you’re ahead like that. Also material ones, like: tired.””

I also understand that you have to shed your skin, your brand, the lineup to evolve. That doesn't mean we fans have to like it. When an artist is done with a certain situation, they should have the courage to move on, whether fans like it or not. Otherwise it really is like living a slow death, the noose and handcuffs Stephen wore on that last show.

““The rest of the group have wanted to reunite for years; nobody has ever fully explained why they broke up in the first place. I phone guitarist Scott Kannberg and ask him about this. He tells me how much he misses playing their old songs. Kannberg (who performed in Pavement under the moniker Spiral Stairs) cryptically says they broke up because ‘Malkmus got tired of it’ and feared the band would become a cliché. Whenever he talks about Malkmus, it feels like he’s describing someone distant—someone he thinks about yet barely knows. He never even refers to him by his first name. ‘Maybe Pavement is just not as important to him as it is to me,’ Kannberg says toward the end of our conversation. ‘That’s probably all it is. But I’ve come to accept that.’””

I really feel for Scott here. I've been through something like it. Not as a bandmate, but as the bandleader, the one writing the songs and holding the thing together.

Last year I had a band member leave. It wasn't a shock; he'd hinted at it before. I talked him into staying a few times. We’d played together for over two years. He'd been to my house, had dinner with my family, I met his parents, who were happy for him being in my wonderful band. I liked the guy... He was fun to have on stage. And then, suddenly, he was gone.

He missed what turned out to be our last show together because (allegedly) his cat died and he flew home. We played as a trio in the rain instead. The show was fine, but a bit sad. I think we played to 10 people. Afterwards we took a long break. It felt like a breakup, and for weeks I kept asking myself what I could have done differently. Why would someone walk away from something that had been good for so long?

So I can't imagine what it was like for Pavement—to have that band, after a decade of building a legacy, just quietly dissolve. No big fight, no official announcement. Just gone.

That's how it was with The Police, too. During the Synchronicity tour, legend has it they agreed they couldn't get any bigger. And then Sting simply put out a solo record. Malkmus did the same, forming The Jicks in Portland. No press release. No drama. Just... over.

And that's the strange part. The fans wanted more. Scott clearly wanted more. The rest of the band probably could have kept going. But I get it: being in a band can feel suffocating, even if you're playing your own songs. You grow up. You want to be free. You get tired of compromises. And at a certain point—especially if you're the one holding the keys—you don't have to compromise anymore.

That's why Terror Twilight hits so hard in hindsight. For all the tension, it's a tender record. Songs like "Spit on a Stranger" and "Major Leagues" sound like parting gifts, almost too gentle for a band on the verge of collapse.

So why would the primary songwriter, the leader, end something so good? That's the question I keep circling back to as a fan. And of course, it's not really mine to ask. I'm not Stephen. I'll never know what it's like to be celebrated for a body of work decades later, to be worshipped for songs you wrote in your twenties. He doesn't owe anyone an explanation. I'm grateful for what we got. But still, I wonder.

Because the stories from that last tour don't paint a rosy picture: Malkmus traveling separately from the band, refusing to ride with them. Telling bandmates through his guitar tech that he was "done with Pavement." Covering his head with a shirt, calling himself "the little bitch" (...I shouldn’t, but I find this funny on some level). Distancing himself from the creative process, then finally walking away.

It sounds harsh, even mean. But anyone who's been in a band knows how it goes. Bandmates can drive you insane. And when you have the freedom to walk away, sometimes you do.

Being in a band is like any job—you work closely with people you didn't necessarily choose. Sometimes it clicks, sometimes it doesn't. Creative tension can push you to brilliance or push you apart. It's fragile. When the balance tips, it's easy to say F this, and move on. Bands are fucking hard.

But when they're good? There's nothing better. Pavement was the best band in the world. They still are to me—not just the best '90s band, not just the best indie band. My favorite band, period. I can put them on repeat forever. Just last month I drove seven hours to LA and back listening to nothing but Pavement, and I never got bored.

That's the magic they left behind. And maybe that's why the quietness of their breakup still stings.

Why didn't Pavement want to "make it"?

I've been thinking a lot about something from Louder Than You Think (which I've seen three times now). There's a moment where Gary Young's wife teases him: "All fame and no fortune." Gary just looks sad, shrugs, and says, "I tried." It's a small but telling scene.

It's known that Gary quit, partly because unlike him, Pavement didn't want to "sell out." The whole affair raises the question: Why wouldn't they want to make it?

I personally never got into music to be rich or famous. I wanted to make a living at it, sure, but the way Nirvana did it before they went supernova (Kurt's original goals were to sell like 300,000 copies of a record like Sonic Youth. Like Pavement, he didn't expect it to go beyond that). I don't care about the celebrity trappings. But I do care about my music connecting with people—more than a handful. I want people to know the songs, to recognize the work. I still do.

“What made Pavement so out of step with its time (and ours) was its seemingly indifferent attitude toward success. ”

For Pavement, I think it was about fun, community, and making music that resonated creatively. Indie rock was about being understood on an artistic level. I get that. But still, why not also want to get paid?

Stephen Malkmus has said they didn't want to take A&R money or give up control. Bob Nastanovich has mentioned they knew they couldn't "fulfill" on being the next Nirvana, that they couldn't follow through. I wonder if that was projection, because Stephen clearly could follow through in terms of songwriting. He knows how to write a commercial hit, even if Pavement's only "minor" one was "Cut Your Hair"—an early '90s track that got some MTV and 120 Minutes play, but never crossed into full mainstream success.

“There was always a really gradual progression that made sense to all of us and was really encouraging, you know, because the Nirvana thing had happened and because that was like the time when you know, most eligible to be signed, banned stuff is floating around. and none of that really hit me too much, because I just didn’t really deal with the business. I just dealt with things that were real. Like, what are we going to do? And like, when are we going to do it?

I just knew at the same time, at the level of professionalism and the approach and the whole way that we did things and the reluctance to like get together and take things more seriously, that we were never going to go to a place that Nirvana went to or a lot of bigger bands. So I always assumed that it was really silly that major label people and other factors were trying to take our band seriously, because I knew the songs weren’t ever going to be huge radio hits, and I just knew that we weren’t going to be able to follow through.”

Another layer to this is the fear of what a major label deal might mean. If you sign, does that mean executives breathing down your neck, telling you "I don't hear a single," pushing you into things you don't want to do? You're working for them, and that advance is a loan you have to pay back. I've never been in an A&R office, so maybe it really is that stifling.

But a major also gives you marketing muscle—exposure you simply don't get otherwise. That's the trade-off.

Pavement seemed averse to that trade-off, maybe because they felt they couldn't be themselves in that system. That's the only conclusion I can draw—only the band could give the real answer. I do know they bristled when Gary went rogue, asking labels for a million-dollar deal, as shown in Louder Than You Think.

““If we had signed to Gold Mountain management, or if we had signed with Geffen, maybe Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain sells 750,000 copies instead of 250,000 copies. But it was really just the difference between being Pavement or being Weezer,” Malkmus says. “I never had a great deal of confidence in my ability to write hits. There’s a formula to that, and I’m not a good chorus writer. I’m better at the verses. Sometimes I don’t even get to the chorus.””

I'd argue that Malkmus can very easily write hits. All of their greatest songs and the album he cites above probably could have charted higher with major label marketing muscle.

Maybe he just couldn't bring himself to write the kinds of songs that make Weezer a more accessible, if not cloying, band. I love Weezer but they write crowd-pleasers, and their more recent albums are so full of that sort of thing that for me it makes them less musically interesting. I think being seen and heard as an artist is important to Malkmus, and he's said in interviews what was most important to him was creative control, and maintaining control of his/the band's "brand," i.e. artistic integrity.

“I just knew at the same time, at the level of professionalism and the approach and the whole way that we did things and the reluctance to like get together and take things more seriously, that we were never going to go to a place that Nirvana went to or a lot of bigger bands. So I always assumed that it was really silly that major label people and other factors were trying to take our band seriously, because I knew the songs weren’t ever going to be huge radio hits, and I just knew that we weren’t going to be able to follow through.””

Bob said in the excellent Slow Century documentary that the band could not be professional enough to deliver on the demands that come with being on a major label, but again, I think having fun and creating music on their own terms that connected with fans that really "got it" was what they truly cared about. And in your 20s, that's leading quite possibly the most fulfilling life you can as a musician, before families come along and the additional compromises and responsibilities that come along with the "career, career, career" Malkmus laments in their highest-charting song, "Cut Your Hair," a cynical look at music and fandom as a business.

I often wonder if they could have crossed to the mainstream and kept delivering songs as iconic as the ones they did in their 10-year run. Maybe not. Maybe they did the right thing.

““We’re not trying to stay underground or trying to be big. We’re just existing.” ”

The band was often compared to Nirvana and seen as their indie rock successors, but that never happened. Nirvana carefully found a label that fit, signed, and went on to become the biggest band in the world. In some ways, Kurt's early death was in some ways a cautionary tale Malkmus was smart enough to avoid as someone who really cared about his music.

As I wrote in my blog post about Nirvana's legacy, Kurt cared deeply about who his fans were, his indie rock cred, and of course the integrity of his music. It's hard to reconcile this with the suits in the label office, knowing their motives are completely different.

How many more hits could Stephen have written with proper label support? Would Pavement have survived longer with more mass appeal and resources behind them?

We'll never know. But that's part of the mystery of Pavement—this cocktail of aversion to "making it," devotion to their indie ethos, and a sense that they'd rather burn out on their own terms than risk becoming something they didn't want to be.

Is the weapon found in this obscure interview?

After posting this piece, I kept digging—watching live shows, interviews, falling asleep to Pavement docs. It's become my nightly ritual.

I recently came across this obscure 2001 interview with Stephen (I am always surprised by the low view count of such things), which may provide the strongest clue yet as to why SM walked away.

Around 4 minutes in, SM talks about his upcoming solo record, and how we (Pavement) “agreed 10 years is a good time to finish.”

For some reason, the sad guitar music underneath the interview only lends to the pensive, somewhat downbeat vibe here. After Terror Twilight was completed, “I had to get to work again” (on new songs), he says, assuring fans that they sound similar to Pavement, more like Crooked Rain—“more upbeat, catchier, a little faster…”

He talks about his new band, a three-piece. “A three-piece is tough,” he muses. “It’s hard to be a three-piece.” There’s footage of said trio playing a show. Not bad. Not Pavement.

““I wanted to do something like that for a while. But I had trouble getting that energy towards the end in Pavement. With this new band, it was very fresh, like we more excited to work with each other, maybe. And I consciously made the song structures more traditional. I kept it simple in some ways because it was our first record. And I was also playing to the strengths of the people I was playing with.” ”

Here the picture becomes clearer. And again, it’s ironic I found this video after this post initially went live. Here's what I'd been looking for. Not the whole picture, but closer.

We know bands fall apart for many reasons. I can’t even explain them all. Hell, I just learned my drummer is going to start playing with a new band yesterday.

Yes, there is burnout. Wanting to do something different (I can’t imagine playing the same songs for 10 years straight, TBH). Taking it as far as you can before hitting a ceiling, etc.

But as the singer/songwriter of the band, the interview really resonated with me as a musician. Because the main theme here is about wanting to go in a certain direction, and not feeling that support from your homies. Unfortunately it’s something I went through recently with my own band.

Let’s cover the interview first, then my own personal experience and reflections. Again from a small-time indie rocker, not a rock star. But still, I can relate.

It’s recorded before his solo LP comes out, before his solo career evolved into the Jicks. The usual brat swagger, the dry humor, the sarcasm, the attitude is missing. Instead, it’s a more vulnerable, humbled, even reticent SM.

I feel for him in this.

There’s a sense of “Not sure where this is going but hope it works out.” None of us like that Pavement broke up, but it takes tremendous courage to move forward this way.

If my band breaks up, nobody gives a shit. But this is Pavement, often called the greatest indie band of all time. Can you imagine the pressure, starting something new? What if the fans hate it? What if they’re indifferent?

There’s footage of a live show as a trio, just SM and a bassist and drummer. He admits “trios are hard.” He knows this could fail. He knows it’s not Pavement.

He also very tellingly speaks to what this article explores; why he ultimately walked away.

He talks about wanting a more conventional classic rock sound (“but good”) but clearly got pushback on that approach, which made Crooked Rain arguably their best and most accessible album. The energy wasn’t there to support wanting to go in that direction.

This is a dealbreaker for the primary songwriter. I’m sure it wasn’t the only breaking point, but it is likely the main one. When you’re not feeling that support, when you’re stuck and want to shift gears… backwards, forwards, it doesn’t matter.

It’s enough to deal with fans and critics’ expectations. Having to deal with internal pushback is almost worse. Bands and bandmates ride such fine lines between transactional and deeply, deeply personal. They have to like the material. They have to believe in you. When they don’t like a new song or some new direction you might want to explore, it is very difficult to work with.

It stings. It’s hard not to take personally, at least for me. It’s certainly creatively frustrating and impossible to work with if the others are digging their heels in. The lack of enthusiasm in rehearsals can feel very deflating and awkward.

As a musician and bandleader myself, I am all too aware of the dynamics at play here and why even the best bands eventually fall apart. Sometimes it takes a few months, years, or in Pavement’s case, almost a decade. But something like this friction is a dealbreaker. It’s made me want to work with new people for sure.

After one of my band members left after a few happy years, I wanted to strip down—less people to manage, more aggressive sound. But they weren't into the trio format, which fed into my own insecurities as a frontman and guitarist. One of them even said they couldn't see doing this long-term. I didn't care. I was tired and didn't want to audition lead guitarists and teach parts all over again. I wanted to hear my new songs better, explore my guitar playing with stripped-down arrangements. Is the trio format ideal? Not always. But it can be great if the band is tight (Green Day, Nirvana, Sugar, Blink-182, Silverchair...)

I explained this would be a temporary thing… Let’s just focus on getting really good as a trio and a guitar player will come along organically. Still the foot-dragging and lack of enthusiasm. Getting that energy back that SM refers to above.

In addition to changing circumstances, new creative needs popping up, musicians also become adults. Bands are really gangs or packs of youths. Like Pavement at the beginning of their 10-year run, ghey often start in high school or college, and it’s you against the world. Your’e aligned in your mission under this company brand name.

But that eventually wears off as people strive to find their own personal and artistic identity. It’s natural.

“Creative differences” is the cliche, but at the end of the day, bands are easier when it’s a group of kids vs. adults, because our inclination as adults is to be more settled into our identify, vision and what we want to do with our time, and who we want to spend it with. More options and choices, vs. riding along with circumstance.

Watch the video and it might be the final piece of the puzzle.

Even if that’s true, we’ll never see all the pieces. I’ve learned since writing this piece that the band tends to be pretty tight-lipped about the specific circumstances around it falling apart. I didn’t write this piece to invade anyone’s privacy or open old wounds. I wrote it for me to learn more about Pavement, why I love the band, and why it had to end.

For fellow fans, maybe this provides some closure. Or maybe it just circles back to what matters: the songs themselves, and the fact that for ten years, Pavement was exactly what they needed to be. That's more than most bands ever manage.

What does it all mean

I found a good summary of Pavement in the form of an Apple Music write-up accompanying Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain. Who is this writer? They clearly get it. Give these writers credit for being awesome, Apple Music:

Pavement's second album Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain may be the definitive 1990s indie-rock record, in large part because its lyrical wit and low-key melodic grace feel so tossed-off and casual. The band projected a defiant effortlessness that still sounds incredibly cool today, even without the context of knowing they were deliberately sidestepping the possibility of becoming "the next Nirvana" and dodging a sophomore slump after their 1992 debut, Slanted & Enchanted, was immediately canonized by music critics. They pulled this off mainly by making a bold stylistic pivot from twitchy post-punk and lo-fi artiness to a relaxed stoner vibe, drawing mostly from '70s West Coast psychedelia and the more jangly end of '80s college rock.

By embracing a looseness that had been a liability in Pavement's haphazard early live shows, band leader Stephen Malkmus found his voice and delivered a handful of his most enduring songs—the wistfully romantic but oddly aloof "Gold Soundz," the bratty bubblegum of "Cut Your Hair," and "Range Life," a gentle folk-rock tune that famously doubles as a Smashing Pumpkins diss track. (Billy Corgan stayed mad about that for a long time.) The deep cuts are even better: "Stop Breathin" is a melodramatic epic that conflates a tennis match with trench warfare, "Newark Wilder" is a melancholy ballad about some kind of ambiguous love triangle, and "Unfair" is a sunny punk-rock number satirizing the economic and social tensions between Northern and Southern California. (Somehow this was the second time the band wrote a song about this topic.)

Malkmus sprinkles his songs with homages to every corner of his impeccable record collection, with overt nods to Dave Brubeck on the instrumental "5-4=Unity" and to Buddy Holly's "Everyday" in the verses of the riffy opening track "Silence Kit." But as much as the band calls back to music from the past, it never feels like pastiche or a game of spot-the-references. The band's carefree swagger and nerdy mystique is like an overpowering spice that makes everything sound exactly like Pavement. The shambling style also serves as a cover for Malkmus's remarkable craft and ambition as a songwriter. It's all right there, in every song, but it's all so casual it never feels like they're showing off. The beat goes slack, Malkmus's voice goes flat, and it's all just sleight of hand to distract you from their magic trick.

Pavement today

“Harness Your Hopes” finds new life on TikTok

"Harness Your Hopes" was never meant to be a Pavement anthem—it was a Terror Twilight B-side, recorded during the Brighten the Corners sessions. But thanks to a Spotify algorithm boost in 2017 and a full-on TikTok dance revival in 2020 and again in 2024, the song became their biggest track, ultimately earning Gold certification. The tune was so obscure outside Pavementheads that even SM apparently didn’t even recognize it at first when he heard it being played on Spotify in a gluten-free Portlandia bakery.

In response, the band released a fresh music video, leaned into the moment, and reaffirmed a quirky legacy that's still finding new ways to connect generations.

Sure, maybe it's the "algorithm," or more likely Pavement remains relevant even to a new generation because their music is in a class of its own. Kids only know what's marketed to them. I find it hard to believe that all kids like these days is bland bubblegum pop like Taylor Swift, Katy Perry and the like. We still need great bands like Pavement to fill the void, to make us feel something. Not synthetic pop bullshit but rather music where the band plays their instruments, authors their material, develops their own sound. I think kids are desperately craving that authenticity wherever they can find it, and the kids must be alright if they're leaning into Pavement.

Pavements: a movie as noble, strange and messy as the band itself

Are you still reading? Damn, good job. This is a long-ass blog post but I will agree the subject warrants this level of depth.

And it wouldn't be complete without covering the recent mockumentary (?) Pavements, which I recently, and yes, somewhat reluctantly watched. I admit I had put this off because I wasn't super into the trailer. It looked a bit twee, I'm not into musicals or the whole meta thing in general… but hey, the band was involved, and it included new footage and interviews. How bad could it be?

If you want to see the band put in context, I'd start with the Gary Young documentary, as it's perfect and I don't think anything else needs to be said about Pavement if you're just curious about how it all started and where it all ended up. If you want to get even more current, you'll want to check this out, since it was shot and released in 2023, when they had their most recent reunion tour.

In short, I don't think the musical theater stuff added anything, but I admit to not being a fan of musical theater in general as an art form. Just… why. Anyway…

Then there's the whole Pavement museum thing, which I didn't think really added anything. It amplifies the film’s exploration of Pavement as cultural artifact or curiosity than as a musical band (maybe this is why I just prefer the more straightforward approach of documentaries in general).

Where it got a bit more interesting for me was the "musical biopic" and "making of" stuff. Some scenes of Joe Keery studying SM's soft palette and his resulting impression were fun—the guy really sounds like him, even if to me he doesn't resemble SM much. I also enjoyed the scene of the band backstage after they got pelted with mud at Lollapalooza. It felt raw and real, and Nat Wolff, who plays Scott, is quite good. It convinced me that it happened (I wonder if it actually did).

And I felt Scott's pain at SM's general malaise and indifference about what Pavement was supposed to be (this is around the 1:38 mark if you want to jump to it). Scott wants to be good, respected and successful as they can be, and Stephen continues to question what that means, what it entails. Maybe he's feeling the pressure of delivering on that (although again, I think he tried in his own way with Crooked Rain in particular). It's a painful scene to watch as a fan and musician myself. I feel for both of them, to be honest.

For me, this scene circles back to around 1:00, when SM is being interviewed about Crooked Rain, their second and regularly most accessible and best (to me, anyway) record.

““After Crooked Rain, everyone heard it and they’re like ‘This is gonna be so great. You’re set. This is a proper fuckin’ album. Get ready. Strap it on cause it’s goin off.’ Then I was like ‘Oh, that’s all I have to do. I can just act like I don’t care. It’s gonna be so big.’ It’s what Kurt Cobain would do, too. But then it didn’t happen.””

I can't help but hear him wailing I'm tryin', I'm tryin' I'm trying in "Conduit for Sale." I really think he did on this record and Brighten the Corners in particular, but you can only be true to yourself and write awesome songs before you have to stop short of writing something like "Beverly Hills" or even "Buddy Holly," which Weezer doesn't have a problem doing.

I'm personally glad SM wrote what he wrote when he wrote it and didn't make any compromises to his own standards, and that maybe he's just not able to write songs that would appeal to certain mainstream Weezer or Ed Sheeran fans. Again I doubt that's the case and it doesn't really matter as much as their body of work and legacy as it stands.

I hesitate to include this film in that but that's not my call. Other solid nuggets included any footage of the band, past or current. There's one scene where the real SM tells Scott bluntly his harmonies sound bad and to work on them. It seems pretty cruel, the way it's delivered. Scott is clearly taken aback. It doesn't seem super nice but it's cool they let that one make the final cut. We know SM is capable of being a jerk but that doesn't make it pleasant to see or treat a bandmate or friend that way. Maybe I just feel that way because I think I'm a nice guy and worry a band member would just quit if I talked to them that way. Who knows what degree of assholery I'd be capable of if I were SM or even near famous. It makes you wonder.

In one scene, Scott tells the story of how, in 2008, he was very low on money, divorced and about to start a new job as a bus driver (maybe he got the idea from Bob, who was also a bus driver) when SM called out of the blue informing him that Pavement was going to do a reunion tour. (It's especially funny that Scott does a decent impression of SM's voice). It reminds you of the gap between seeing your musical heroes play to thousands of people and confusing that with earning a decent living (more on this topic of commerce ahead)—sadly the two don't often go hand in hand.

Those scenes stuck out for me, and a fourth. Noah Baumbach (my son's middle name is a homage to him) and Greta Gerwig show up and have a conversation with SM. I don't even remember the content, it's mostly surface fellow celebrity pleasantries. I mean, those two are pretty damn cool in my book so of course they know Pavement on this level. It doesn't matter if it was real or staged, it just seemed sort of irrelevant and the band belonging to that celeb club vs. being those everyday brat outsiders that punk/indie/music nerds like me made it feel like the band was ours and not the shiny happy people's band.

In summary, could've done without the musical and museum stuff. Keep in like 20% of the "music biopic" stuff and any footage of the band and you'd have a tidy hour, maybe 1:15-30 with some additional band performances, which is always going to be way better than anything artificial because it's Pavement and not third party interpretive.

At the end of the day, even though SM was bluntly asked in this film "Why did Pavement break up?", the band is still full of mystery—both the personalities and the music. This is part of their magic. This is part of the magic of the lyrics and their whole approach, even to what it means to be a band.

Double click on almost any aspect of the band and there is some mystery. Even the album art. R.E.M. is very good at this, and while they are heroes to both Pavement and me, they are not as good at this as Pavement. It's part of why I worship them now. I will never write a song as good as most Pavement songs, and I could honestly spend the rest of my life trying, the way SM says that 80% of every one of his songs is just the "fantasy" of his input turning into his output (two songs of mine in particular are my attempt at replicating some sort of "Pavement" style—"Fire Drill" and "Workin' for the Man," but I don't think the latter is that great and I am unsure if the band would even like "Fire Drill," although I do.)

BTW, SM's answer to that interviewer question was a brief something about "interviews and touring," a meta / ironic response, of course (the interviewer seems to get it, which is cool). Of course it's more complicated than that, per Scott's insights above.

I get why SM didn't want to keep going. Hell, I wanted to quit my own band after two years, and one member did. And we played out like once a month, not every day, or twice a day. It's tiring, shows are not done on your time, and it's hard work. Again this doesn't even address the creative aspects of it, feeling boxed in or "the brand" making it difficult to move forward. It doesn't address the money and fame aspects of it, which can feel very cold compared to the purity of sitting down with a guitar and notebook and just creating, or recording with your buds in the studio with no pressure or expectations (SM says something about "What happened to just making this to sell 200 copies" and "fun" in this film).

But there remains the mystery. Economics has so much to do with making art. Maybe running an indie rock band that sells between 100-200K units is simply not sustainable as a job for grown men with families especially. The machine of running a band at that level entails too many other people getting paid. This adds more pressure to sell more units, which becomes more pressure once more units are sold and you start getting past Sonic Youth territory and into Nirvana level "success”. And Kurt spent the rest of his career apologizing for "Nevermind," part of which led to his own tragic and early demise.

So maybe SM, now living in Portland on his own terms, musically and otherwise, knew and knows exactly what he's doing. I already know he's a smart guy, but maybe he's just mega smart to the point where when someone like me starts getting into Pavement all over again to the point of listening to them months on end and writing this blog… I think you get the point.

The music and legacy and leaving it alone when you're supposed to are what matters. You dig too deep to solve the riddle, the mystery, feels impossible and tiring. I'd rather just play the music and hold on to that feeling it makes me feel. If I keep scratching away at everything underneath it starts to feel like a drag. But I can't help it. The music is so good, I just need to know and analyze until that urge just runs out of gas.

Eventually I just want to go back to keeping it simple and listening to the records, hearing SM in particular interviewed because he's very good at not digging this deep himself (or at least pretends to be, although I think he's too smart to overthink this stuff, and why would he when he can write songs this good?)

REUNION TOURS AND PAVEMENT TODAY (2025)

Pavement’s story didn’t end at Brixton. They’ve come back twice now for reunion tours—first in 2010, and again in 2022–23—reminding everyone why their music still matters. Those shows were more than nostalgia trips; they pulled younger fans into the fold while giving longtime listeners the chance to finally hear songs that had lived only on record for decades.

Today, they’re still keeping that momentum going. On September 28, 2025, the band released a new best-of compilation, Hecklers Choice: Big Gums and Heavy Lifters, available digitally now, with CD and vinyl editions due November 14 via Matador Records. Alongside it comes the physical release of the Pavements soundtrack—an odd but fitting mix of live and rehearsal recordings from their 2021 reunion, dialogue from the documentary, and songs from the Slanted! Enchanted! jukebox musical.

They’re also back on the road, with new U.S. and Mexico dates announced. For a band that once seemed permanently allergic to being “a career,” Pavement in 2025 are as present and vital as they’ve been in decades.

And if you need proof, the band just dropped a new live video from the Pavements Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, directed and edited by Robert Greene. Filmed during their 2022–24 reunion tour at the Fonda Theater in Los Angeles, it’s a reminder of just how powerful these songs remain. For longtime fans, it’s moving to see them return to the stage not as a fractured group walking off in handcuffs, but as a band amplifying their legacy in real time. Watching it feels like a kind of happy ending—the breakup unresolved but also redeemed, their story rewritten on their own terms.

Same.

Maybe that’s the irony of Pavement’s story: for all the cryptic endings and missed opportunities, they’ve landed exactly where they’re supposed to be—back on stage, on their own terms. What once felt like a premature fade-out now reads more like a pause, a band reemerging when the time was right. And with a whole new generation hungry for guitar-driven indie rock that actually has grit and wit, Pavement are here to answer the call—still imperfect, still essential, and still unlike anyone else.

One last comment…

In the course of researching this post, I was scrolling through the comments on this live Roskilde video (which are as genuine and wonderful a celebration of the band as it gets, btw). This one really stopped me…

““If only a time machine was a real thing. I wouldn’t care so much. This is the stuff that lasts. This is the stuff that makes real itself.””

Was this some lost passage from one of SM's notebooks? Was it written by someone whose first language was not English? Is it a reference to some Pink Floyd song I might not know about? (I wouldn't be able to quote any Pink Floyd song as I've actively avoided their music since high school).

The sentiment doesn't get lost in the abstract language; in fact it's expressed so beautifully it just made me want to linger on it, like Pavement's music.

For further exploration

There is no shortage of live footage and clips on YouTube, let alone articles that cement the band's legacy. Having sifted through much of that, I wanted to provide a brief list of the materials I think capture the band's spirit and history best, outside of just listening to the music itself, which is where you will likely find the most joy.

That said, the band's history, personalities and performances are varied and legendary, which for me makes it worth exploring artifacts outside their records.

Documentaries